- “So” is commonly used as an adverb, conjunction, interjection, and even a pronoun.

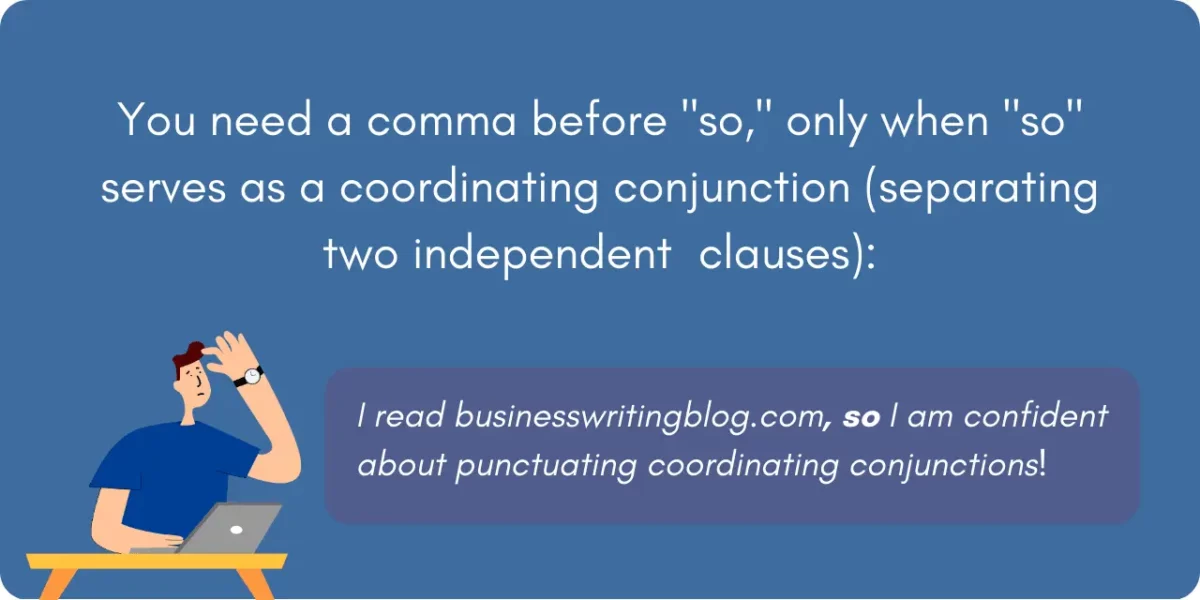

- A comma is required before “so” only when it functions as a coordinating conjunction.

- Coordinating conjunctions join two independent clauses to create a compound sentence.

Do I Need a Comma Before “So?”

The English language often plays fast and loose with rules, causing grief for those learning to speak and write it, even those for whom it is a native tongue. The word “so” is only two letters. Still, it plays various roles within a sentence, including exclusive membership among the seven coordinating conjunctions, often taught in education systems using the mnemonic device “FANBOYS” (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so).

Nonetheless, “so” also enjoys popularity as an adverb, which modifies a verb, adjective, or another adverb (I was so hungry!), and occasionally moonlights as a pronoun, replacing a noun (They are experts; so are we). Other times, it serves as an interjection to start a sentence, as in the title of this article. However, this usage sometimes causes controversy within the grammatical community since, by nature, the word references that something has come before, which is why it makes such an excellent connecting word.

However, “so” only requires a comma immediately before it to satisfy grammatical correctness in a single circumstance: when used as a coordinating conjunction, meaning it connects two independent clauses, like so:

It was starting to rain, so I took out my umbrella.

However, if so is introducing a dependent clause (also known as subordinate clauses), meaning the clause can not stand on its own, the comma is NOT needed:

I took out my umbrella so I could stay dry

What are Coordinating Conjunctions?

There are seven coordinating conjunctions (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so), also known as the aforementioned “FANBOYS.” These connectors join two independent clauses, which are complete sentences with a subject and verb and any additional parts needed to stand alone and make sense. When done correctly, it creates a compound sentence.

To illustrate:

Independent clause + , (FANBOYS) + independent clause = compound sentence

Maliki enjoys peanut butter, but he is allergic to it.

The first independent clause is “Maliki enjoys peanut butter,” and it is proper because it has a subject (Maliki) and a verb (enjoys) and includes “peanut butter” to explain what the boy enjoys, completing the idea. You could slap a period on the end, and it could stand alone as a complete sentence.

The same is true for “he is allergic to it” because it has a subject (he) and verb (is) and includes “allergic to it” to finish the thought.

Now, including the coordinating conjunction connects these two related ideas and gives the reader a clue as to how they are related. “But” indicates a contrasting idea, which is appropriate as there is a positive and a negative – he would love to eat it, except his allergy makes that a risky proposition.

Notice that there must be a comma and a coordinating conjunction. That comma is required when joining two complete sentences to form a compound sentence and must come before the coordinating conjunction. Leaving out either of those two principal components is such a big deal that there is a specific name for each mistake!

- Maliki enjoys peanut butter, he is allergic to it.

We are missing the coordinating conjunction in this variation, so the two ideas are run together with only a comma. This is called a comma splice error.

- Maliki enjoys peanut butter but he is allergic to it.

This example demonstrates a run-on sentence, which occurs when two independent clauses are joined with only a coordinating conjunction, leaving out the comma.

When Do You Use Each Coordinating Conjunction?

As coordinating conjunctions clarify the relationship between two sentences, it is vital to choose the right one, or somebody could misunderstand your intended meaning. The following will help you know when to use each while providing further insight into how they form compound sentences.

For – Explains a Reason

Perhaps the most overlooked of the FANBOYS, “for” enjoyed more significant usage in the past. While you may still see it used in formal writing, people generally substitute its subordinating conjunction counterpart “because” instead, as this coordinating conjunction now sounds unusual in modern society.

- I was thirsty, for I had been out in the sun all day.

The comma and conjunction are bolded, making it easier to see each independent clause and how they can stand alone as complete sentences. The speaker is thirsty, and the reason is that they were out in the heat.

And – Adds an Additional Idea

The most commonly used “and” is relatively easy because you add one idea to another to provide extra information.

- Ricardo likes Zombies, and Cynthia loves Ninjas.

Because “and” is the conjunction of choice, there is no contrast intended here, just two useful bits of information about two different people, in case anyone is interested.

Nor – Joins One Negative Idea with Another

This conjunction joins two similar ideas, much like “and,” but acts almost like the opposite since those two ideas are negative.

- Brian does not like Mandy, nor does he like Tabitha!

“Not” is a clue that this is a negative idea, and nor signifies another negative idea is coming. This is also a rarely used coordinating conjunction, possibly because it is more complicated – for proper usage, the subject and verb appear in reverse order like they do when someone asks a question.

But – Links a Contrasting Idea

This coordinating conjunction signifies that an opposing idea is coming next, like a positive + a negative. We touched on this a bit earlier, so let’s look at another example:

- My friend invited me to the concert, but I didn’t have enough money for tickets.

The first independent clause sounds like good news, especially if the speaker is interested in the performer. However, “but” shows its ugly head, indicating why the person will not be able to attend. What a shame; perhaps he can convince his friend to give him a loan.

Or – Introduces a Choice

Most people understand how to use the word “or” to show a choice; however, one of the most common problems is that they want to use a comma in front of it when “or” does not join two complete sentences.

- We can either have hamburgers, or pizza for dinner.

Why is this a mistake? The first clause can stand alone, yet “pizza for dinner” is not a complete sentence – it is missing a subject (or verb, depending on how you look at it)! It seems minor, but this does not form a compound sentence, so no comma is necessary.

The following examples show proper usage:

- We can have hamburgers for dinner, or we can have pizza.

Now we have a proper choice with two independent clauses.

Yet – Links a Contrasting Idea

Wait a minute, isn’t that what but is for? Right-o! In most cases, yet can be used interchangeably with its counterpart, giving you another option if you need more variety in your sentences.

However, sometimes yet is a better choice when it indicates a situation that may change later.

- Danny has saved enough money to buy a PS5, yet his mother is still at work.

The implication is that Danny is not old enough to drive, so he will need to wait until his mother gets home before realizing his console dream. As his mother will eventually get off work, that difficulty is only temporary.

So – Shows a Result or Effect

Finally – the star of our show. This word takes one independent clause and joins it to another that describes a result. At this point, you should have a pretty good idea of how to use a comma with a coordinating conjunction, so this one should be easy.

In fact, that makes a good sample sentence, as it shows a result:

- You should have a pretty good idea of how to use a comma with a coordinating conjunction, so this one should be easy.

The first independent clause refers to our previous discussion of conjunctions and comma usage that led us to this point, with the hopeful result that you have seen enough examples to have an excellent understanding of how to use a comma with so!

The Difference Between “So” and “So That”

Before we wrap up, a specific circumstance can confuse those trying to decide whether to use a comma in front of “so” or not. Consider the following two sentences:

- John studied hard for the test, so he passed it.

- John studied hard for the test so that he would do well.

Only the first example needs a comma. Why? Looking at each side of the bolded words, you will soon discover that they each seem to join independent clauses.

However, so that is considered a subordinating conjunction, and by nature, that word makes a sentence dependent, forming a complex spaces=”true”>sentence. As that opens the door to a whole new lesson, for simplicity, remember that if “so that” is functioning as a single unit (as opposed to that being a subject pronoun for a clause), you will not include a comma before so.

Here is the difference in how “that” can be used as a subject pronoun starting the second clause versus a subordinating conjunction joining clauses:

- Mom gave me money for the fair, so that is something, at least.

- Mom gave me money for the fair so that I could buy a funnel cake.

The Main Takeaway

“So” is commonly used as an adverb, conjunction, interjection, and even a pronoun. You need a comma before “so” when the word is used as a coordinating conjunction, connecting two independent clauses.

For example:

The project proved to be easier than initially thought, so the team finished early.

If so introduces a dependant clause, however, no comma is needed:

She rushed to the office so she wouldn’t be late.